I think it is about time the community begins to hold scientists accountable for their claims in the public media regarding hydrino research, just as surely as we do for climate research. Christopher Sirola, a professor in the Department of Physics & Astronomy at the University of Mississippi, has made the following claims:

(1.) "That there is absolutely no evidence for fractional energy levels"

(2.) "if I had strong evidence like this, I would submit it to standard journals in the field, allow other physicists to review my results, and hold the debate in a professional forum." The implicit, but unstated accusation here is that Randell Mills has not submitted evidence to standard journals in the field to allow other physicists to review his results.

Both of these claims feel true. Perhaps Sirola wants them to be true, because it would save him the trouble of learning something new. They satisfy what Stephen Colbert might call "truthiness" and in recent years, scientists who have done absolutely no work in the field of hydrino chemistry have made similar comments in the popular press.

Let's check professor Sirola's facts, starting in reverse order:

(2.) In fact, contrary to popular opinion, Randell Mills and his team of scientists have published over 100 experimental journal articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals over the last 25 years, claiming evidence for fractional energy levels of hydrogen. If you don't believe me, here is a partial list. Caution, it is really fucking long.

*Mills, R., J. Lotoski, W. Good, and J. He. (2014) “Solid Fuels that Form HOH Catalyst.” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39: 11930-11944 DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.05.170

*Mills, R., J. Lotoski, J Kong, G Chu, J He, and J Trevey. (2014b) “High-Power-Density Catalyst Induced Hydrino Transition (CIHT) Electrochemical Cell.” Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 39: 14512-14530. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.06.153.

Mills, R.L.; Booker, R.; Lu, Y. (2013). "Soft X-ray continuum radiation from low-energy pinch discharges of hydrogen." J Plasma Physics. doi:10.1017/S0022377812001109.

Mills, R.L.; Nansteel, M.; Good, W.; Zhao, G. (2012). "Design for a BlackLight Power Multi-Cell Thermally Coupled Reactor Based on Hydrogen Catalyst Systems". Int. J. Energy Research 36: 778–788. doi:10.1002/er.1834.

Mills, R.L.; Lu, Y. (2011). "Time-Resolved Hydrino Continuum Transitions with Cutoffs at 22.8 nm and 10.1 nm". Eur. Phys. J. D 64: 65–72. doi:10.1140/epjd/e2011-20246-5.

Mills, R.L.; Zhao, G.; Akhtar, K.; Chang, Z.; He, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, G.; Lotoski, J.; Chu, G. (2011). "Thermally Reversible Hydrino Catalyst Systems as a New Power Source". Int. J. Green Energy 8: 429–473. doi:10.1080/15435075.2011.576287.

*Mills, R.L.; Lotoski, J.; Zhao, G.; Akhtar, K.; Chang, Z.; He, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, G.; Chu, G. (2011). "Identification of New Hydrogen States". Physics Essays 24: 95–117. doi:10.4006/1.3544207.

*Mills, R.L.; Zhao, G.; Good, W. (2011). "Continuous Thermal Power System." Applied Energy 88: 789–798. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.08.024.

*Mills, R.L.; Zhao, G.;Akhtar, K.; Chang, Z.; He, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, G.; Lotoski, J.; Chu, G. (2010). "Thermally Reversible Hydrino Catalyst Systems as a New Power Source". Prep. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc., Div. Fuel Chem. 55 (2): 252.

*Mills, R.L.;Lu, Y. (2010). "Hydrino Continuum Transitions with Cutoffs at 22.8 nm and 10.1 nm". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35: 8446–8456. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.05.098.

Mills, R.L.; Akhtar, K. (2010). "Fast H in Hydrogen Mixed Gas Microwave Plasmas when an Atomic Hydrogen Supporting Surface Was Present". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35: 2546–2555. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.12.148.

Mills, R.L.; Akhtar, K.;Zhao, G.; Chang, Z.; He, J.; Hu, X.; Chu, G. (2010). "Commercializable Power Source Using Heterogeneous Hydrino Catalysts". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 35: 395–419. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.10.038.

Mills, R.L.; Lu, Y.; Akhtar, K. (2010). "Spectroscopic Observation of Helium-Ion- and Hydrogen-Catalyzed Hydrino Transitions". Cent. Eur. J. Phys 8: 318–339. doi:10.2478/s11534-009-0106-9.

Mills, R.L.; Good, W.; Jansson, P.; He, J. (2010). "Stationary Inverted Lyman Populations and Free-Free and Bound-Free Emission of Lower-Energy State Hydride Ion formed by and Exothermic Catalytic Reaction of Atomic Hydrogen and Certain Group I Catalysts". Cent. Eur. J. Phys 8: 7–16. doi:10.2478/s11534-009-0052-6.

Akhtar, K.; Scharer, J.; Mills, R.L. (2009). "Substantial Doppler Broadening of Atomic Hydrogen Lines in DC and Capactively Coupled RF Plasmas". J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 42 (13): 135207–135219. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/42/13/135207.

Mills, R.L.; Good, W.; He, J. (2009). "Excess Power and the Product Molecular Hydrino H2(1/4) Generated in a K2CO3 Electrolysis Cell". Electrochimica Acta 54: 4229–4236. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2009.02.079.

Mills, R.L.; Akhtar, K. (2009). "Tests of Features of Field-Acceleration Models for the Extraordinary Selective H Balmer alpha Broadening in Certain Hydrogen Mixed Plasmas". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 34: 6465–6477. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2009.05.148.

Mills, R.L.; Zhao, G.; Akhtar, K.; Chang, Z.; He, J.; Lu, Y.; Good, W.; Chu, G.; Dhandapani, B.; (2009). "Commercializable Power Source from Forming New States of Hydrogen". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 34: 573–614. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.10.018.

Mills, R.L.; (2008). "Hydrogen Plasmas Generated Using Certain Group I Catalysts Show Stationary Inverted Lyman Populations and Free-Free and Bound-Free Emission of Lower-Energy State Hydride". Res. J. Chem Env. 12(2): 42–72.

Mills, R.L.; Dhandapani, B.; Akhtar, K. (2008). "Excessive Balmer alpha Line Broadening of Water-Vapor Capacitively-Coupled RF Discharge Plasmas". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 33: 802–815. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.10.016.

Mills, R.L.; He, J.; Nansteel, M.; Dhandapani, B. (2007). "Catalysis of Atomic Hydrogen to New Hydrides as a New Power Source". Int. J. of Global Energy Issues (IJGEI) Special Edition in Energy Systems 28 (2-3): 304–324. doi:10.1504/IJGEI.2007.015882.

Mills, R.L.; Zea, H.; He, J.; Dhandapani, B.; (2007). "Water Bath Calorimetry on a Catalytic Reaction of Atomic Hydrogen". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 32: 4258–4266. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.06.017.

Mills, R.L.; He, J.; Lu, Y.; Nansteel, M.; Chang, Z.; Dhandapani, B.; (2007b). "Comprehensive Identification and Potential Applications of New States of Hydrogen". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 32(14): 2988–3009. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.03.035.

*Mills, R.L.; He, J.; Chang, Z.; Good, W.; Lu, Y.; (2007a). "Catalysis of Atomic Hydrogen to Novel Hydrogen Species H-(1/4) and H2(1/4) as a New Power Source". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 32(13): 2573–2584. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.02.023.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B. (2006). "Evidence of an energy transfer reaction between atomic hydrogen and argon II or helium II as the source of excessively hot H atoms in radio-frequency plasmas". J. Plasma Physics 72 (4): 469–484. doi:10.1017/S0022377805004034.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Mayo, R.M.; Nansteel, M.; Dhandapani, B.; Phillips, J. (2005). "Spectroscopic Study of Unique Line Broadening and Inversion in Low Pressure Microwave Generated Water Plasmas". J. Plasma Physics 71 (6): 877–888. doi:10.1017/S0022377805003703.

Mills, R.L.; Dhandapani, B.; He, J. (2005). "Highly Stable Amorphous Silicon Hydride from a Helium Plasma Reaction". Materials Chemistry and Physics 94 (2-3): 298–307. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.05.002.

Mills, R.L.; He, J.; Chang, Z.; Good, W.; Lu, Y.; Dhandapani, B. (2005). "Catalysis of Atomic Hydrogen to Novel Hydrides as a New Power Source". Prepr. Pap.—Am. Chem. Soc. Conf., Div. Fuel Chem. 50 (2).

*Mills, R.L.; Sankar, J.; Voigt, A.; He, J.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B. (2005b). "Role of Atomic Hydrogen Density and Energy in Low Power CVD Synthesis of Diamond Films". Thin Solid Films 478: 77–90.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P. (2004). "Stationary Inverted Lyman Population and a Very Stable Novel Hydride Formed by a Catalytic Reaction of Atomic Hydrogen and Certain Catalysts". J. Opt. Mat. 27: 181–186. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2004.02.026.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B.; Good, W.; Jansson, P.; Nansteel, M.; He, J.; Voigt, A. (2004). "Spectroscopic and NMR Identification of Novel Hydride Ions in Fractional Quantum Energy States Formed by an Exothermic Reaction of Atomic Hydrogen with Certain Catalysts". Euro. Phys. J.: Applied Physics 28: 83–104. doi:10.1051/epjap:2004168.

Mills, R.L.; Lu, Y.; Nansteel, M.; He, J.; Voigt, A.; Good, W.; Dhandapani, B. (2004). "Energetic Catalyst-Hydrogen Plasma Reaction as a Potential New Energy Source". Division of Fuel Chemistry, Session: Advances in Hydrogen Energy, Prepr. Pap. — Am. Chem. Soc. Conf 49 (2).

*Mills, R.L.; Sankar, J.; Voigt, A.; He, J.; Dhandapani, B.; (2004). "Synthesis of HDLC Films from Solid Carbon". J. Mater. Sci. 39: 3309–3318. doi:10.1023/B:JMSC.0000026931.98685.59.

Mills, R.L.; Lu, Y.; Nansteel, M.; He, J.; Voigt, A.; Dhandapani, B.; (2004). "Energetic Catalyst-Hydrogen Plasma Reaction as a Potential New Energy Source". Division of Fuel Chemistry, Session: Chemistry of Solid, Liquid, and Gaseous Fuels, Prepr. Pap.—Am. Chem. Soc. Conf. 49 (1).

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Nansteel, M.; He, J.; Chen, X.; Voigt, A.; Dhandapani, B. (2003). "Characterization of an Energetic Catalyst-Hydrogen Plasma Reaction as a Potential New Energy Source". Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Fuel Chem. Prepr. 48 (2).

*Mills, R.L.;Sankar, J.; Voigt, A.; He, J.; Dhandapani, B.; (2003b). "Spectroscopic Characterization of the Atomic Hydrogen Energies and Densities and Carbon Species During Helium-Hydrogen-Methane Plasma CVD Synthesis of Diamond Films". Chemistry of Materials 15: 1313–1321. doi:10.1021/cm020817m.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P. (2003). "Extreme Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Helium-Hydrogen Plasma". J. Phys. D, Applied Physics 36: 1535–1542. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/316.

Mills, R.L.; Chen, X.; Ray, P.; He, J.; Dhandapani, B. (2003). "Plasma Power Source Based on a Catalytic Reaction of Atomic Hydrogen Measured by Water Bath Calorimetry". Thermochimica Acta 406 (1-2): 35–53. doi:10.1016/S0040-6031(03)00228-4.

Mills, R.L.; Dhandapani, B.; He, J.; (2003). "Highly Stable Amorphous Silicon Hydride". Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 90 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1016/S0927-0248(03)00107-7.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Mayo, R.M.; (2003). "The Potential for a Hydrogen Water-Plasma Laser". Applied Physics Letters 82 (11): 1679–1681. doi:10.1063/1.1558213.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; (2003a). "Stationary Inverted Lyman Population Formed from Incandescently Heated Hydrogen Gas with Certain Catalysts". J. Phys. D, Applied Physics 36: 1504–1509. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/312.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B.; He, J.; (2003). "Comparison of Excessive Balmer alpha Line Broadening of Inductively and Capacitively Coupled RF, Microwave, and Glow Discharge Hydrogen Plasmas with Certain Catalysts". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 31 (3): 338–355. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.812340.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Mayo, R.M.; (2003d). "CW HI Laser Based on a Stationary Inverted Lyman Population Formed from Incandescently Heated Hydrogen Gas with Certain Group I Catalysts". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 31 (2): 236–247. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.810174.

*Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Dong, J.; Nansteel, M.; Dhandapani, B. (2003). "Spectral Emission of Fractional-Principal-Quantum-Energy-Level Atomic and Molecular Hydrogen". Vibrational Spectroscopy 31 (2): 195–213. doi:10.1016/S0924-2031(03)00013-4.

Mills, R.L.; He, J.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B.; Chen, X. (2003). "Synthesis and Characterization of a Highly Stable Amorphous Silicon Hydride as the Product of a Catalytic Helium-Hydrogen Plasma Reaction". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 28 (12): 1401–1424. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(02)00293-8.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P. "A Comprehensive Study of Spectra of the Bound-Free Hyperfine Levels of Novel Hydride Ion H-(1/2), Hydrogen, Nitrogen, and Air". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 28 (8): 825–871. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(02)00167-2.

*Mills, R.L.; Nansteel, M.; Ray, P.; (2003b). "Excessively Bright Hydrogen-Strontium Plasma Light Source Due to Energy Resonance of Strontium with Hydrogen". J. Plasma Physics 69: 131–158. doi:10.1017/S0022377803002113.

Mills, R.L.; (2003). "Highly Stable Novel Inorganic Hydrides". J. New Materials for Electrochemical Systems 6: 45–54.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; (2002). "Substantial Changes in the Characteristics of a Microwave Plasma Due to Combining Argon and Hydrogen". New Journal of Physics 4: 22.1–22.17. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/4/1/322.

*Mayo, R.M.; Mills, R.L.; Nansteel, M. (2002). "Direct Plasmadynamic Conversion of Plasma Thermal Power to Electricity". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 30 (5): 2066–2073. doi:10.1109/TPS.2002.807496.

*Mills, R.L.; Nansteel, M.; Ray, P.; (2002b). "Bright Hydrogen-Light Source due to a Resonant Energy Transfer with Strontium and Argon Ions". New Journal of Physics 4: 70.1–70.28. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/4/1/370.

Mayo, R.M.; Mills, R.L.; Nansteel, M. (2002). "On the Potential of Direct and MHD Conversion of Power from a Novel Plasma Source to Electricity for Microdistributed Power Applications". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 30 (4): 1568–1578. doi:10.1109/TPS.2002.804170.

Mills, R.L.; (2002). "Highly Stable Novel Inorganic Hydrides from Aqueous Electrolysis and Plasma Electrolysis". Electrochimica Acta 47 (24): 3909–3926. doi:10.1016/S0013-4686(02)00361-4.

*Mills, R.L.; Dayalan, E.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B.; He, J. (2002). "Comparison of Excessive Balmer alpha Line Broadening of Glow Discharge and Microwave Hydrogen Plasmas with Certain Catalysts". , J. of Applied Physics 92 (12): 7008–7022. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.812340.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B.; Mayo, R.M.; He, J.; (2002). "Comparison of Excessive Balmer alpha Line Broadening of Glow Discharge and Microwave Hydrogen Plasmas with Certain Catalysts". J. of Applied Physics 92 (12): 7008–7022. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.812340.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; Dhandapani, B.; Nansteel, M.; Chen, X.; He, J. (2002). "New Power Source from Fractional Quantum Energy Levels of Atomic Hydrogen that Surpasses Internal Combustion". J. Mol. Struct. 643 (1-3): 43–54. doi:10.1016/S0022-2860(02)00355-1.

Mills, R.L.; Dong, J.; Good, W.; Ray, P.; He, J.; Dhandapani, B. (2002). "Measurement of Energy Balances of Noble Gas-Hydrogen Discharge Plasmas Using Calvet Calorimetry". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (9): 967–978. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(02)00004-6.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P.; (2002). "Spectroscopic Identification of a Novel Catalytic Reaction of Rubidium Ion with Atomic Hydrogen and the Hydride Ion Product". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (9): 927–935. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(02)00002-2.

Mills, R.L.; Voigt, A.; Ray, P.; Nansteel, M.; Dhandapani, B.; (2002). "Measurement of Hydrogen Balmer Line Broadening and Thermal Power Balances of Noble Gas-Hydrogen Discharge Plasmas". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (6): 671–685. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00172-0.

Mills, R.L.; Greenig, N.; Hicks, S. (2002). "Optically Measured Power Balances of Glow Discharges of Mixtures of Argon, Hydrogen, and Potassium, Rubidium, Cesium, or Strontium Vapor". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (6): 651–670.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P. (2002). "Vibrational Spectral Emission of Fractional-Principal-Quantum-Energy-Level Hydrogen Molecular Ion". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (5): 533–564. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00145-8.

*Mills, R.L.; Nansteel, M.; Ray, P.; (2002c). "Argon-Hydrogen-Strontium Discharge Light Source". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 30 (2): 639–652. doi:10.1109/TPS.2002.1024263.

Mills, R.L.; (2002). "Spectral Emission of Fractional Quantum Energy Levels of Atomic Hydrogen from a Helium-Hydrogen Plasma and the Implications for Dark Matter". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (3): 301–322. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00116-1.

Mills, R.L.; Ray, P. (2002). "Spectroscopic Identification of a Novel Catalytic Reaction of Potassium and Atomic Hydrogen and the Hydride Ion Product". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 27 (2): 183–192. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00093-3.

Mills, R.L.; Dayalan, E. (2002). "Novel Alkali and Alkaline Earth Hydrides for High Voltage and High Energy Density Batteries". Proceedings of the 17th Annual Battery Conference on Applications and Advances: 1–6. doi:10.1109/BCAA.2002.986359.

Mills, R.L.; Good, W.; Voigt, A.; Dong, J. (2001). "Minimum Heat of Formation of Potassium Iodo Hydride". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (11): 1199–1208. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00051-9.

Mills, R.L. (2001). "Spectroscopic Identification of a Novel Catalytic Reaction of Atomic Hydrogen and the Hydride Ion Product". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (10): 1041–1058. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00041-6.

Mills, R.L.; Dhandapani, B.; Nansteel, M.; He, J.; Voigt, A.; (2001). "Identification of Compounds Containing Novel Hydride Ions by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (9): 965–979. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00027-1.

Mills, R.L.; Onuma,T.; Lu, Y.; (2001). "Formation of a Hydrogen Plasma from an Incandescently Heated Hydrogen-Catalyst Gas Mixture with an Anomalous Afterglow Duration". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (7): 749–762. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00004-0.

*Mills, R.L.; (2001a). "Observation of Extreme Ultraviolet Emission from Hydrogen-KI Plasmas Produced by a Hollow Cathode Discharge". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (6): 579–592. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00122-1.

*Mills, R.L.; Dhandapani, B.; Nansteel, M.; He, J.; Shannon, T.; Echezuria, A.; (2001). "Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Hydride Compounds". Int. J. of Hydrogen Energy 26 (4): 339–367. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00113-0.

Mills, R.L. (2001b). "Temporal Behavior of Light-Emission in the Visible Spectral Range from a Ti-K2CO3-H-Cell". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (4): 327–332. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00099-9.

Mills, R.L.; (2001). "Observation of Extreme Ultraviolet Hydrogen Emission from Incandescently Heated Hydrogen Gas with Strontium that Produced an Anomalous Optically Measured Power Balance". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 26 (4): 309–326. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00098-7.

*Mills, R.L.; (2000b). "Synthesis and Characterization of Potassium Iodo Hydride". Int. J. of Hydrogen Energy 25 (12): 1185–1203. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00037-9.

*Mills, R.L.; Dong, J.; Lu, Y.; (2000c). "Observation of Extreme Ultraviolet Hydrogen Emission from Incandescently Heated Hydrogen Gas with Certain Catalysts". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 25: 919–943. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00018-5.

Mills, R.L.; (2000). "Novel Inorganic Hydride". Int. J. of Hydrogen Energy 25: 669–683. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(99)00076-2.

* (2000) BlackLight Power Technology: A New Clean Energy Source with Potential for Direct Conversion to Electricity. Global Foundation Inc, Nov 26-28, 2000. Presented at International Conference on Global Warming and Energy Policy, Ft. Lauderdale, FL. CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

*Mills, R.L.; (2000). "Novel Hydrogen Compounds from a Potassium Carbonate Electrolytic Cell". Fusion Technology 37 (2): 157–182.

*Mills, R.L.; Good, W.; (1995). "Fractional Quantum Energy Levels of Hydrogen". Fusion Technology 28 (4): 1697–1719.

*Mills, R.L.; Good, W.; Shaubach, R. (1994). "Dihydrino Molecule Identification". Fusion Technology 25 (103).

*Mills, R.L.; Kneizys,S. (1991). "Excess heat production by the electrolysis of an aqueous potassium carbonate electrolyte and the implications for cold fusion". Fusion Technology 20 (65).

Okay, now that we got that out of the way (whew), I wanted to add a few more by outside primary authors including Jonathan Phillips (from UNM and LANL), and Joseph Conrads, who was possibly the most respected plasma physicist in the world, before his passing a few years ago.

Conrads, H, R Mills, and Th Wrubel. (2003) “Emission in the deep vacuum ultraviolet from a plasma formed by incandescently heating hydrogen gas with trace amounts of potassium carbonate.” Plasma Sources Sci Technol 12: 389–395.

Driessen, N. M., E. M. van Veldhuizen, P. Van Noorden, R. J. L. J. De Regt, and G. M. W. Kroesen. (2005) “Balmer-alpha line broadening analysis of incandescently heated hydrogen plasmas with potassium catalyst.” In XXVIIth ICPIG, Eindoven, the Netherlands. 18-22 July.

Phillips, Jonathan, Chun Ku Chen, and Randell Mills. (2008) “Evidence of energetic reactions between hydrogen and oxygen species in RF generated H2O plasmas.” Int. J. of Hydrogen Energy 33, 10: 2419–2432.

Phillips, Jonathan, C.K. Chen, Kamran Akhtar, Bala Dhandapani, and Randell Mills. (2007) “Evidence of catalytic production of hot hydrogen in RF generated hydrogen/argon plasmas.” Int. J. of Hydrogen Energy 32, 14: 3010–3025.

Phillips, J.; Chen,C. K.; Akhtar, K.; Dhandapani, B.; Mills, R.L.; (2007). "Evidence of Catalytic Production of Hot Hydrogen in RF-Generated Hydrogen/Argon Plasmas". Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 32(14): 3010–3025. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.01.022. CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

Phillips, Jonathan, Randell MIlls, and Xuemin Chen. (2004) “Water bath calorimetric study of excess heat generation in ‘resonant transfer’ plasmas.” J. App. Phys. 96, 6: 3095–3102.

Most of the articles are in the IJHE, but the editors of two dozen other journals have also published papers of Mills, his team, and collaborators.

But wait, these are just journal articles. Maybe I should also add issued technical or validation reports by outside physicists who were given the opportunity to review Mills' results? These do not hold the same level of scientific weight as journal articles, yet they are an important part of the scientific discourse if the authors are, like Sirola, a professor allied with a respected institution. Unlike Sirola, these authors actually did some work before they opened their mouth.

Bykanov, Alexander. (2010) “Validation of the observation of soft x-ray continuum radiation from low-energy pinch discharges in the presence of molecular hydrogen.” Technical report, GEN3 Partners.

Copeland, Terry. (2012) “Catalyst Induced Hydrino Transition (CIHT) Electrochemical Cell Validation.” Technical report, January 5.

Craw-Ivanco, M.T., Tremblay, R.P., Boniface, H. A., Hilborn, J. (1994) “Calorimetry for a Ni/K2CO3 Cell” Chemical Engineering Branch, Chalk River Laboratories. June.

Crouse, Gilbert. (2014) “Differential Scanning Calorimeter Analysis of Hydrino-Producing Solid Fuel” Auburn University Department of Aerospace Engineering.

GEN3 Partners, (2009) “GEN3 Validation Report” Water Flow Calorimetry, Experimental Runs and Validation Testing for BlackLight Power, Inc.” Technical Report. August.

Gernet, Nelson, and Robert Shaubach. (1994) “Nascent Hydrogen: An Energy Source.” Technical report, Thermacore, Inc., Prepared for Aero Propulsion and Power Directorate, Wright Laboratory, Air Force Material Command (ASC), Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio 45433-7659. SBIR Contract No. F33615-93-C-2326, Report No. 11-1124.

Glumac, Nick. (2012) “Final Consultant Report” Technical report. January 21.

. (2014), “Report from Visit to BlackLight Power on Friday, January 17, 2014” Technical report.

. (2014b) “Scientific Test Report” Mechanical Science & Engineering Department, University of Illinois. Technical report. April.

Haldeman, C.W., E.D. Savoye, G.W. Iseler, and H.R. Clarke. (1995) “Excess Energy Cell Final Report ACC Project 174.” Technical report.

Jacox, M. G., Watts, K. D., (1993) “The Search for Excess Heat in the Mills Electrolytic Cell” Idaho National Engineering Laboratory, January 7.

Jansson, Peter, Amos Mugweru, KV Ramanujachary, and Heather Peterson. (2009) “Anomalous Heat Gains From Multiple Chemical Mixtures: Analytical Studies of “Generation 2” Chemistries of Black-Light Power Corporation.” Technical report, Rowan University, November.

Jansson, Peter, Amos Mugweru, KV Ramanujachary, and John Schmaizel. (2010) “Anomalous Heat Gains from Regenerative Chemical Mixtures: Characterization of BLP Chemistries Used for Energy Generation and Regeneration Reactions.” Technical report, Rowan University, November.

Jansson, Peter, Ulrich Schwabe, Matthew Abdallah, Nathaniel Downes, and Patrick Hoffman. (2009) “Water Flow Calorimetry, Experimental Runs and Validation Testing for BlackLight Power, Inc.” Technical report, Rowan University, May.

Marchese, Anthony, Peter Jansson, and John Schmalzel. (2002) “The Black-Light Rocket Engine: Phase I Final Report.” Technical report, College of Engineering, Rowan University. Phase I Study funded by the NIAC CP 01-02 Advanced Aeronautical/Space Concept Studies Program.

Mugweru, Amos, KV Ramanujachary, Heather Peterson, and John Kong. (2009a) “Report on Synthesis and Studies of “Generation 2” Lower Energy Hydrogen Chemicals.” Technical report, Rowan University.

Mugweru, Amos, K.V. Ramanujachary, Heather Peterson, John Kong, and Anthony Cirri. (2009b) “Synthesis and Characterization of Alkali Metal Salts Containing Trapped Hydrino.” Technical report, Rowan University.

Neterov, Sergei and Kryukov, Alexei. (1993) “In re Application of Mills Appl. No. 07/825, 845” MPEI Cryogenics Center. 26 February.

Niedra, Janis. (1996) “Replication of the Apparent Excess Heat Effect in a Light Water Potassium Carbonate-Nickel Electrolytic Cell. Technical Memorandum No. 107167.” Technical report, NASA.

Payne, Philip. (2010) “OH Radical.” Technical report. April 16.

Peterson, S.H., (1994) “Evaluation of Heat Production from Light Water Electrolysis Cells of Hydrocatalysis Power Corporation” Technology Department, Westinghouse STC. February 25.

Phillips, Jonathan, Julian Smith, and Kurtz, Stewart. (1996) “Report on Calorimetric Investigations of Gas-Phase Catalyzed Hydrino Formation.” Technical report, Department of Chemical Engineering, Penn State University.

Phillips, Jonathan. (1996) “Consulting Report: Additional calorimetric examples of anomalous heat from physical mixture of K/carbon and Pd/carbon.” Technical report, Department of Chemical Engineering, Penn State University.

Pugh, James, and Dayalan, Ethirajulu. (2012) “Evaluation of Electrical Power Generation by BlackLight Power’s Catalyst Induced Hydrino Transition (CIHT) Cells” The ENSER Corporation. Technical report. April 4.

Ramanujachary, K. V., (2011) “Validation of Electrical Power Generation by Second-Generation CIHT Technology” Technical report. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Rowan University. November.

. “Validation of SF-CIHT Technology” (2014) Technical report. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Rowan University. February.

Shaubach, Robert, and Nelson Gernet. (1993) “Anomalous Heat from Atomic Hydrogen in Contact with Potassium Carbonate.” Technical report, Thermacore.

Spittznagel, John. (1994) “Review of ESCA Evidence for Fractional Quantum Energy Levels of Hydrogen” Science and Technology Center, Westinghouse. Letter. January 18.

Weinberg, Henry. (2012) “CIHT Validation Report” Technical report. January.

. (2014) “Report of Visit to BlackLight Power on January 14 and 15, 2014” Letter. January 29.

Wow, that's probably enough for now. I think it's fair to say that Sirola was wrong on this particular point. Let's move on.

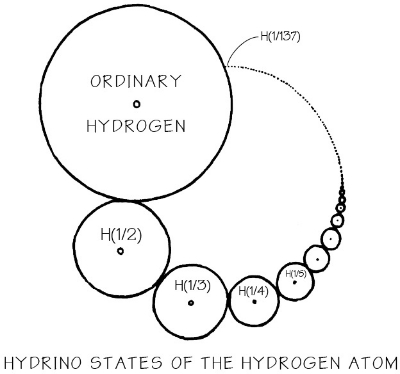

(1) I dare say that if Sirola bothered reading any of the above studies, he might find some evidence there, but I can briefly summarize some of it for him in advance.

a) NMR identification of upfield shifted peaks in hydrino hydride compounds

b) XPS identification of hydrinos and hydrino hydride ions.

c) EUV emissions in hydrogen plasmas corresponding to hydrino transitions, and matching unidentified lines from the sun and the interstellar medium

d) Emissions of bell-shaped continuum radiation corresponding to hydrino transitions in pinch-discharge plasmas

e) Formation of excessively bright plasmas, emitting primarily in the EUV, with extremely low initiation voltages, with long-lasting afterglow durations, and with unexpectedly high line broadening in all directions, indicating the plasma is chemically-assisted, but only performing with certain hydrogen and mixed-hydrogen plasmas. Some of these plasmas also exhibit sustained lyman or balmer series inversion.

f) High heat gains from several generations of electrochemical cells with hydrino catalysts.

g) High heat gains from a variety of "batch" calvet cells with hydrino catalysts

i) new compositions of alkali and alkaline earth hydrino hydrides from X-ray crystal diffraction studies

j) identification of rovibrational transitions in hydrogen plasmas and in trapped crystal structures corresponding to hydrino molecules

k) identification of spin-nuclear coupling of hydrino atoms in far-infrared absorption studies of cryogenically cooled hydrogen

l) And, I should mention, high-current induced explosions of capsules emitting primarily in the EUV and soft X-ray wavelength.

This is some of the evidence that has been proposed. Not all of it.

I should point out that this evidence has not been widely scrutinized by the scientific community outside the dozens of researchers directly involved. This would be the next step to general acceptance, or rejection, of the evidence.

I realize that there is often a high barrier for investigating new discoveries. And I realize that there are aspects of Mills's proposal which, on first glance, smack of pseudoscience: new states of hydrogen, new energy technology, new theories. It sets off all the warning bells.

And I sympathize with the larger point of Sirola's article, which is to say that I have very little patience for fringe science and pseudoscience.

But in this particular case, the claims of Mills, his team, and his collaborators, may be grounded in genuine experimental realities that will force us to learn something new about the hydrogen atom.

Brett Holverstott

author of the forthcoming book: Randell Mills and the Search for Hydrino Energy